ProTip: When Should I Attack or Defend?

Question: I hit the ball fairly well but often am unsure of whether to ‘attack’ or ‘defend’ while playing a point. What’s a basic strategy to make this choice simple?

Ninety percent of players spend their time on court trying to improve their technique, and particularly so when their serve or backhand breaks down under pressure or they commit a lot of errors. Often the “cure” suggested by their pro is more stroke lessons to either improve the suspect stroke or cut down on errors. The next 9% or so figure out what the strengths of their game are: strong serve, volley, forehand weapon, speed around court, and try to play their strength(s) as much as possible against their opponent’s weakness. In case you have been doing the maths, the last 1% have actually figured out how to play/adjust against their opponent’s game.

Regardless of your strengths, your basic game starts with a clear understanding of when to ‘attack’ or ‘defend’ since ultimately success in tennis goes to the player who hits the ball over the net and into the court the last time! The so-called ‘pusher’ understands this very well and wins when his/her opponent overplays the ball — and their errors and frustration increase exponentially .

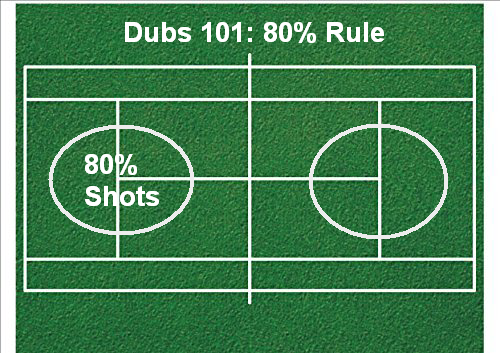

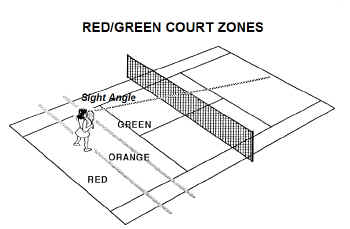

Many years ago, Billie Jean King wrote about a simple ‘traffic light strategy’ of dividing the court into green (safe), yellow (caution) and red (danger) zones. The strategy was based on a player’s ability to get close enough to the net to safely hit down on the ball.

Here’s a simple figure I prepared some time ago to illustrate the basic principle:

It’s fairly obvious that a taller player has an obvious advantage by being able to see ‘over the net’ from deeper in the court. It also follows why the pusher wins if you are trying to constantly attack from the baseline — the odds are stacked against you!

You’ll have noticed that in the modern game, the top players use more topspin to drive the ball up and over the net when closer to the baseline to overcome the disadvantage of being deeper in the court.

To be certain you understand the principle here’s a side view:

Hence, the simplest game plan of all then, is to figure out where your red, yellow, and green zones are and play accordingly.

When you are in the red zone, defend and keep the ball in play; in the yellow zone, hit approach shots to take control of the net by moving into your green zone. When in the green zone with a ball bouncing higher than the net, attack!

This game plan also goes by another name — percentage tennis! It may not be spectacular as ‘first strike tennis’, but success has a nice warm feel to it!

And even if you are trying to play ‘first strike tennis’, there are many times — and particularly on big points, when ‘first strike tennis’ is NOT your best option! Just watch how Roger and Rafa play the big points in tie breakers or when down set point or behind on serve.

Become THE ‘smarter player’. It’s always nice to come off with a win regardless of how poorly/well you hit the ball. In fact Brad Gilbert wrote a book about playing smart when you are outgunned. He called it –“Winning Ugly”.

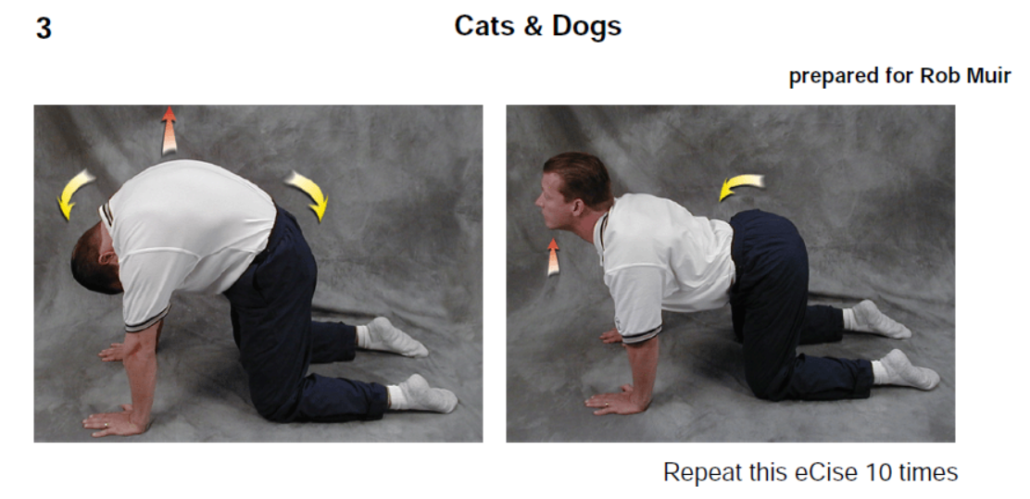

Rob Muir, USPTA

MTC Tennis Whisperer

Contact Rob Muir