The intensity, athleticism, and drama of finals tennis were on full display at the 2024 Manly Seaside Championships!

By New Year’s Eve afternoon, champions were crowned in the premier events, delivering thrilling performances across all categories.

Finals Results:

- Men’s Singles: Connor defeated Roger 7-6(5), 6-4.

- Women’s Singles: Linda edged Ellen in a nail-biting 7-5, 4-6, 7-5 battle.

- Men’s Doubles: Jay and Jordan triumphed over Lachlan and Andre, 6-3, 6-2.

- Women’s Doubles: Sienna and Sarah claimed victory over Ruby and Jenna, 6-3, 6-3.

- Mixed Doubles: Ellen and Andrew overcame Sienna and Takek, 7-6, 6-1.

Congratulations to all the players for their extraordinary efforts, and kudos to the club for organizing a stellar event. Even the weather cooperated, allowing tennis to shine as the ultimate winner. Special appreciation goes to the club’s volunteers, easily identifiable in their stylish t-shirts, for their seamless coordination. A big thank-you to Shelley for capturing and sharing event highlights and photos on the club’s Facebook page.

It was a privilege to witness most of the finals, and the large crowd certainly enjoyed the exceptional level of tennis on display.

Highlights from the Finals Matches:

Women’s Singles Final

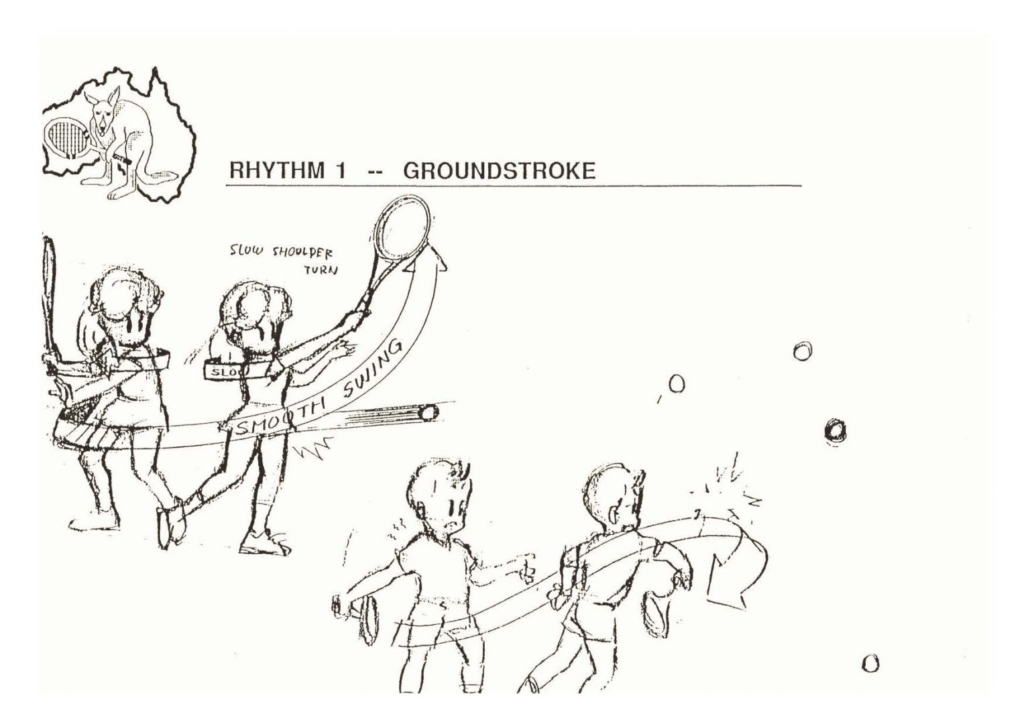

Arguably the match of the tournament, the Women’s Singles final saw both players battling intensely in the deciding set, each with a legitimate shot at victory. Linda, a wildcard entry armed with powerful groundstrokes, displayed remarkable composure under pressure to edge past Ellen. Notably, Ellen later redeemed herself with a title win in the Mixed Doubles event.

Men’s Singles Final

The Men’s Singles final was a thrilling clash of athleticism and baseline power. Roger’s elegant one-handed backhand—a display Federer would undoubtedly admire—was pitted against Connor’s consistent two-hander. The first set was a high-stakes battle that culminated in a tiebreak, where Connor’s strategic forays to the net proved decisive. The second set revealed signs of fatigue in Roger after a week of intense competition. Sensing the opportunity, Connor applied relentless pressure, finally breaking serve in the 10th game to seal the match. As an unseeded entrant, Connor showcased exceptional resilience and tactical precision throughout the week, securing a well-deserved victory.

Men’s Doubles Final

The experienced duo of Jay and Jordan showcased their mastery in doubles strategy, outmaneuvering the younger pair of Lachlan and Andre. Despite Lachlan’s reliable serve, its lack of variety allowed Jay to repeatedly target Andre, who struggled to anticipate and handle shots at the net. The seasoned pair capitalized with classic doubles tactics, dominating at the net and securing a straight-sets victory.

Women’s Doubles Final

Sarah and Sienna’s dominance at the net proved insurmountable for Ruby and Jenna. Their cohesive teamwork and superior court coverage earned them a well-deserved title. Sarah, more aptly nicknamed the “Iron Maiden,” displayed remarkable stamina over a week of matches, although her commitment to her partner in the A grade Mixed Doubles may have hindered her performance in the Women’s Singles semifinal. She lost a close three set match to Linda when she tired in the third set..

Mixed Doubles Final

The Mixed Doubles final concluded with Ellen and local hero, Andrew, demonstrating outstanding synergy to defeat Sienna and Takek. Ellen’s adaptability across multiple events was particularly impressive as she capped her tournament with a well-earned title.

The 2024 Manly Seaside Championships embodied the spirit of tennis—camaraderie, competition, and excellence. Tennis emerged as the true winner of this annual event. Here’s to another year of spectacular matches and unforgettable moments!

Click here for All Event Finals Results